1. Origins of the Cossticks

A Multitude of Spellings

During the mid to late 1700s it was not uncommon for people to be what we would today term as “illiterate” – at least in terms of their ability to read and write. Undoubtedly people of the 1700s would be shocked at our ignorance about many of their life skills. Books were rare possessions in many households, and writing was not often required in daily life. People did not know how to spell words - there was no need to know – and this extended even to not knowing precisely how to spell one’s own name. Often, the only occasion when knowledge of the spelling of one’s surname was needed was when a marriage, baptism or burial was registered at the local church and that was frequently left to the Vicar to do. The Vicar, although usually better educated than most of his parishioners, tended to write the names as they were pronounced.

The ancestors of the Cosstick family were no exception and when they had need to attend a local church to register a baptism, marriage or burial, they told the Vicar the name so that he could write it in the register. “How do you spell it?” he might ask, as we still do today, even with names we hear quite regularly. It would appear that the parents were sometimes not too sure. They knew what their name sounded like but they did not know exactly how to spell it.

The result of this uncertainty was that the name was written in Parish Registers as Costick, Cosstick, Caustick, Coustick, Coulstock, Cowstick, Cowstock, Copestick and other variations. Even within the registers of baptisms for the children of the same family the name could vary from year to year. In some of the registers the minister was so uncertain that he wrote two variations of the spelling side by side just in case – Cosstick OR Cowstick he wrote . Over several generations the children of families adopted the peculiar spelling that had been registered for themselves and passed it on to their children.

The Woodcutters

Whatever the spelling, it appears that the Cossticks probably descended from the early woodcutters of Sussex. The origin of the name can be found in a combination of the Old French word "couper", meaning "to cut", and the Old English word "stikka", or “stakka” meaning a wooden stick or stake . In other words - a woodcutter or stake cutter, an occupation for which there had been a great demand in Sussex for many centuries.

It has been suggested that the name Cowstick originates from Cowstock’s Wood in the Danehill Hundred of Sussex . But then Cowstock’s Wood itself was called Cousticks in 1724 and it is thought that this in turn derived from the family of John de Cokstock, whose name later occurred as Custok and Coustock .

The vast majority of Cowsticks, Costicks and Coulsticks, if we rely upon the frequency of the names in Parish Registers, lived in the villages in the southern Weald of Sussex - Hurstpierpoint, Albourne, Chiltington, Clayton, Keymer, Fletching, Edburton, to name but a few. The earliest records of these names in parish baptism records come from Albourne, where a Thomas Coulestocke was baptized on 28 October 1559 , and Fletching, where an Elner Coulstock was baptized on 22 June 1567 . A family of Coulstouke’s also lived at Eastbourne from 1568 until 1603 .

As early as 1295 a Geoffrey Coupstack appears in the register of the freemen of the City of York, with a John Copestake appearing in 1474. The Copestake variation on the name tended to concentrate around Yorkshire.

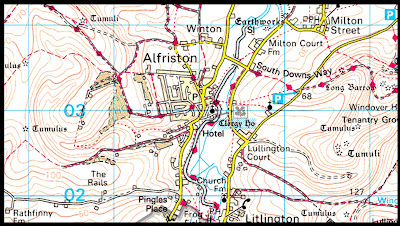

As for the branch of the family in which we are interested - whose names varied between Colestock, Coulstick, Caustick and Cosstick, as well as others - they gradually moved in a south easterly direction, from East Chiltington in the southern Weald in the mid 1600s, to Hamsey, just north of Lewes, in the early 1700s, then to Alfriston and Litlington by the mid 1700s, and finally to the coast at Seaford by the late 1700s.

We might ask what the Cossticks did at these villages. Perhaps they did not actually live in the villages. Perhaps they lived on nearby farms or estates and simply took their children to the village church to be baptized. Or went there themselves to be married. And later, to be buried. In fact, if we take the origin of the name as being an indication of occupational origins then it is easy to imagine the earliest members of the family lived the life of nomadic forest workers or charcoal burners in the Weald .

It seems not possible to accurately trace the ancestors of the Cossticks to a time earlier than the sixteenth century. Again, the origin of the name, a combination of early English and French words, suggests perhaps a combination of Saxon and Norman ancestors. But whether they were recent immigrants - the Saxons arriving in Sussex around 477 AD , and the Normans in 1066 - or older, perhaps Celtic, inhabitants, can be the subject of pure speculation. Perhaps the legendary history of the Medieval Cossticks roaming the Sussex woods like Robin Hood might be written one day.

There appears to be no reference to the Cosstick, or similar, names in the Domesday survey, taken soon after the Norman conquest in 1066, and this suggests that the name either did not exist as such, or that its holders were itinerant, nomadic forest workers who escaped the interest of the Domesday commissioners . The villages of Chiltington, Hamsey, Laughton and Alfriston, where the Cossticks later registered their baptisms and marriages, certainly existed at the time of the Domesday survey.

Sussex Timber

Centuries ago thousands of acres of woodlands in Sussex were cut down by a society hungry for timber. The same happened in other parts of England. The same happened around the Mediterranean. Society needed timber. Timber was used to build houses, to build wagons, to build ships. Timber was also used simply to burn - as firewood. The demand for timber has barely diminished over the centuries. The sources of suitable timber have diminished and timber cutters have now moved into areas once untouched - the rainforests and mountains of nearly every country. The removal of timber has reached such proportions that the ecological balance of the planet is now under threat.

But people were ignorant of such environmental impacts two hundred years ago. Or two thousand years ago. Or were they? The Romans, in removing the forests of Northern Africa, soon witnessed the effect the advancing desert had upon once thriving cities, such as Leptis Magna. The Venetians eventually used up most of their timber building their navy and had to institute a form of forest management. The Weald of central Sussex was once covered in dense forests. When the Romans arrived in Sussex in 43 AD the Wealden forest stretched for 120 miles . Once the forest covered perhaps three-quarters of the county. Today it is barely one quarter, although even that makes Sussex one of the most heavily wooded counties of England .

The Romans built a number of forts around the coast of southeastern England to provide some protection against invasion as well as guidance for ships. When the Saxons arrived four hundred years later they nominated five key coastal towns to protect the South East of England against Danish invasion . Later, the Normans, under William the Conqueror, gave these five towns - the Cinque Ports - a special status by separating them from their counties, Kent and Sussex, and placing them under the jurisdiction of a Warden. Each of the five towns had smaller towns affiliated with it. The Normans also built a series of castles along the coast, not only for defence against invasion but to overawe the local inhabitants .

The role of providing the sea defence of southern England brought not only status to the Cinque Ports, but also a price. During the time of Edward the First, for example, the towns were required to supply no fewer than fifty seven war ships, fully equipped and manned, at their own cost .

The building of warships placed huge demands upon the resources of the towns. To make just one war ship required a vast amount of timber. A Venetian galley of the mid fifteenth century used fifty beech trees for the oars, three hundred pines and firs for planks and spars, and three hundred mature oaks for the hull timbers . The English did not use galleys, but their fighting and merchant ships would have required equally massive quantities of high quality timber. It is estimated that up to two thousand trees were needed for one of the larger warships .

The building of warships placed huge demands upon the resources of the towns. To make just one war ship required a vast amount of timber. A Venetian galley of the mid fifteenth century used fifty beech trees for the oars, three hundred pines and firs for planks and spars, and three hundred mature oaks for the hull timbers . The English did not use galleys, but their fighting and merchant ships would have required equally massive quantities of high quality timber. It is estimated that up to two thousand trees were needed for one of the larger warships .Warships required not just timber, they required armaments. Throughout the Weald of Sussex were hundreds of iron smelters whose main products were cannon and shot. The smelting process required charcoal, up to 250 tons of timber to produce 13 tons of iron . And so oak trees were cut down and burnt to produce charcoal . At one time the Admiralty expressed concern that so much timber was being cut down to make charcoal to make the cast iron cannons that there would be nothing left to build the ships themselves .

There were furnaces and forges scattered right through the forests of the Weald. In time some members of the Cosstick family had gathered enough wealth to branch out from the woodcutting origins and in 1578 Samuel Coulstocke and John Smith leased the forge and furnace of Petworth Manor. This forge was located in the Great or Michel Park of the Manor, and the furnace on the northern border of the Frith .

Earlier in the century, in 1546, it is recorded that Robert Monke and Robert Cowstock were keepers at the forest and had “yerely for their wages, every of them xls with the kepyng of serteyne cattall there”. At the time Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral controlled the estate .

The Sussex iron industry reached its peak in the early 17th century, by which time most of the forest had been cleared. The discovery of abundant coal supplies to the north of England, and the diminishing timber supplies in Sussex contributed to the decline of the industry during the 18th century. Today only remnants of the forests remain in places like St Leonards, Ashdown and Worth.

The Forest of Worth, in the north west Weald, once extended as far south as Cuckfield and possibly to Ditchling, and probably included the present-day woodlands of Crabbet, Wakehurst, Worth, Balcolme and Cuckfield. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there was a wild tract of land now known as Copthorne Common, which was frequented by “lawless characters such as horse stealers and smugglers”. In fact, many former forest and iron workers were forced into unemployment as the timber and iron industries gradually moved elsewhere. Some took to illegal activities, such as smuggling, in their attempt to provide for themselves and their families . Late in the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth the Worth Forest was cut up into residential estates and eventually required an Act or Parliament in 1828 to protect what was left .

Much of the woodlands of Sussex remain in a form that is known as “standard-with-coppice”. Oaks for the upper storey but beneath them are trees that have been cut down to the stock in order to force the growth of slender poles. It is a practice known as coppicing and gives a regular supply of poles, fencing and fuel. The term coppicing, like the name of the Cossticks, comes from the French couper. The trees are cut in November, cleared up in the following April, and left to grow again for another seventeen years .

Apart from the few Cosstick ancestors whose names by chance were recorded in the annals of the great estates what did the others do? Times were changing, albeit slowly, and gradually some members of the family sought work closer to the villages of Sussex.

Thomas of Edburton, Chiltington and Hamsey

John Coulstock, or Colestock, and Margaret Court, or Covert, were married at Edburton, a town to the south west of Hurstpierpoint in the Sussex Weald, on 16 May 1659 . They had several sons. The first son, Thomas Coulstock was baptized on 6 January 1662 at Edburton . The second, John Colestocke, was baptized at Edburton on 20 May 1663. They were followed by another son, Thomas Colestocke, baptized on 12 July 1666, and then Jacob and William, both on 2 May 1673 .

At around the same time, in the town of Hamsey, there lived the family of William Coulstock and his wife. William, a yeoman originally from Framfield, was buried at Hamsey on 10 May 1654. His widow, from Laughton, was buried at Hamsey on 13 March 1659. It seems possible that they had a son, Thomas of Chiltington, who was buried at Hamsey on 14 September 1680, and that this Thomas also had sons, William and John, and a daughter Grace .

On 8 February 1682 a Thomas Coulstock , married Susannah Townsett at the village of East Chiltington . It is not known for certain who the parents of this Thomas were. He might have been the son of John Coulstock and Margaret Court of Edburton. He roughly fits the birth date of their son Thomas who was baptised in 1666 in which case he may have married young. On the other hand he might have been the son of William Coulstock and his wife from Hamsey. William died in 1654 and if Thomas had been born in that year he would have been twenty-eight at the time of his marriage.

Thomas and Susannah subsequently had at least five children. The first, also named Thomas, was baptized on 17 February 1683 at East Chiltington . He was followed by William, baptized on 12 May 1686, and Richard on 16 May 1688, both at Laughton a village some miles to the east of East Chiltington. Next was Samuel, born on 8 April 1694 back at East Chiltington, and Charity, born in 1699, also at East Chiltington .

When he was aged about thirty-one, the third child of Thomas and Susannah, Samuel Coulstick, went to Hamsey, just north of Lewes, where he married Ann Holman on 15 November 1725 . Samuel and Ann subsequently had at least three children. The first, Samuel Coulstick, was born early in 1728 and privately baptised at Hamsey on 27 May 1728. The next, Thomas Cowstick, was born early in 1731, and baptised at Hamsey on2 May 1731 . The different spelling of the surname probably came about through ignorance of how it was spelt and the Vicar’s imagination when it came to filling in the Parish Registers.

A third child, Eden, is listed as being baptised on 27 June 1742, also at Hamsey. It seems likely that there would have been other children between Thomas and Eden.

It seems that Samuel Coulstick died in July 1746 and was buried at Hamsey on 6 July of that year . His son Samuel would have been eighteen at the time, and Thomas would have been fifteen. The sons decided to move to the south east, closer to the coast – Thomas Cowstick to Litlington and Samuel Coulstick to Alfriston - both villages being only a few kilometres apart on opposite sides of the Cuckmare River.

The Woodcutters

Thomas Cowstick of Litlington

At the village of Litlington, a few kilometres north east of Seaford, across the Cuckmare River, Thomas Cowstick married Susan Howell on 29 January 1754. Their children included Reuben, baptized on 19 September 1756; Samuel, on 23 October 1757; Mary, 11 November 1759; John, 28 February 1762; Thomas, 22 June 1767; William, 18 February 1770, and David and Christopher, both baptized on 20 April 1772 .

Nothing further is known of the first son Rueben. A Samuel Cowstick is listed as having married Ann (no surname) and subsequently having at least two children baptized at Cowden in Kent - Elizabeth, on 28 May 1780 and Sarah on 1 November 1788 . However, this would appear to be a different Samuel, as the second son of Thomas and Susan married Elizabeth Reed and they subsequently had nine children - Mary, Thomas, two Sarah’s, Samuel, John, Elizabeth, Ann and Richard . A number of the descendants of this family have been traced down to the present day and are still living in Sussex .

The fifth child, William, possibly married Elizabeth at Litlington and had at least two children, both registered under the name of Cowstock - Thomas, baptized there on 26 January 1794, and Sally, baptized on 1 July 1798 .

Nothing further is heard of Mary, John, David and Christopher.

Samuel Coulstick of Alfriston

At the village of Wilmington, a few kilometres north west of Litlington, Thomas Cowstick’s brother, Samuel Coulstick married Elizabeth Collingham on 27 February 1750. Their children included Thomas, baptized at nearby Alfriston on 12 August 1750; Ann, 3 August 1751; Elizabeth, 30 September 1753; Mary, 12 October 1755; a second Thomas, 21 July 1757; John, 13 January 1760; Samuel, 18 April 1762; and Sampson, 3 May 1767 .

At the village of Wilmington, a few kilometres north west of Litlington, Thomas Cowstick’s brother, Samuel Coulstick married Elizabeth Collingham on 27 February 1750. Their children included Thomas, baptized at nearby Alfriston on 12 August 1750; Ann, 3 August 1751; Elizabeth, 30 September 1753; Mary, 12 October 1755; a second Thomas, 21 July 1757; John, 13 January 1760; Samuel, 18 April 1762; and Sampson, 3 May 1767 .

The first son, Thomas, died young and was buried at Alfriston on 6 October 1750 . More of the second Thomas shortly.

The eldest daughter, Ann, married Thomas Phillips at St Leonard’s at Seaford on 8 August 1773. Thomas Williams, the Curate at the church, wrote her name as Cowstick, which she confirmed with a cross . The Coulsticks of Alfriston were apparently not known for their literacy.

The rest of this chapter is in the book.

Footnotes

Full references and sources are available for this information and are published in the book. Please email me if you would like source references.

No comments:

Post a Comment