3. The Emigrants and Goldseekers

In 1848 J. Allen, of Warwick Lane, Paternoster Row, London, published a small booklet titled The Emigrants' Friend or Authentic Guide to South Australia in which the various Australian colonies were described in some detail for the benefit of intending emigrants . It pictured England as an over taxed country where the ordinary man and his family had little hope of advancement; a country where a lifetime's toil could be wasted; where domestic servants were treated like slaves; where the labourer faced old age in the poor house; where men were imprisoned for trying to feed their families; a country where rents, rates and taxes kept a man impoverished and without hope. It was the England portrayed by Charles Dickens in his novels.

In 1848 J. Allen, of Warwick Lane, Paternoster Row, London, published a small booklet titled The Emigrants' Friend or Authentic Guide to South Australia in which the various Australian colonies were described in some detail for the benefit of intending emigrants . It pictured England as an over taxed country where the ordinary man and his family had little hope of advancement; a country where a lifetime's toil could be wasted; where domestic servants were treated like slaves; where the labourer faced old age in the poor house; where men were imprisoned for trying to feed their families; a country where rents, rates and taxes kept a man impoverished and without hope. It was the England portrayed by Charles Dickens in his novels.

By contrast the Australian colonies offered hope. They offered the chance to own property; to employ others; to earn fair wages; and to pay no taxes. They offered men independence, freedom and confidence.

Each colony had its own peculiar benefits and disadvantages and the Emigrants' Friend sought to picture each as fairly as possible so that the emigrant might make up his own mind according to his own desires and expectations. It warned of promises made by governments and ship owners who sought to attract more trade and settlement, and it warned of promises of cheap land, pointing out that in Australia a single sheep might require four acres of land to survive. After considering the situation of each colony the publishers expressed their preference for the Port Phillip District, or Australia Felix, which, in 1848, was not a separate colony but part of New South Wales.

Port Phillip was located centrally between New South Wales, Tasmania and South Australia and was therefore in an excellent position for trade and supply of commodities. It was the most luxuriant of all of the Australian districts and surpassed the others in the fact that the fruitful portion of the district was greater than the unfruitful. Its climate was “delicious” and resembled a “perpetual spring”. Port Phillip was pictured as a district that raised and expended its wealth with care and reward. The method of selling land in Port Phillip was carefully controlled, unlike the situation in South Australia, where speculation had resulted in disaster. Melbourne, the main town, was only eleven years old and already boasted 13,000 inhabitants who were supplied with all the necessary shops, churches and public institutions. The total population of the district was around 39,000 persons, of whom, the Emigrants' Friend took care to point out, vast numbers were emancipated convicts who had obtained partial freedom but were not permitted to return to England.

No other Australian district could boast of consumer items at a price cheaper than Port Phillip and meat and potatoes were always plentiful, even to the point of being wasted. On the other hand, while prices were cheap, wages were much higher than elsewhere. The picture painted by the Emigrants' Friend was clearly attractive and the publishers concluded that Port Phillip was best suited to the Englishman of small capital and family. It was a “land of plenty, but a land of industry a land of good income and no taxes”.

Between 1852 and 1856 six of the Cosstick brothers from Surrey, England, emigrated to Melbourne, Victoria. By then the Port Phillip District had been granted the status of a separate colony. The Cossticks may have read the glowing description published in the Emigrants' Friend, or in some similar publication, and had undoubtedly heard other favourable reports about the colony. But the immediate lure was gold. News of the Victorian gold discoveries had reached England within a few months of the discoveries being made in 1851, although there had been speculation for several years that gold was to be found. By early 1853 thousands of gold seekers were on their way to Australia.

The Colonization Circular No. 13 of March 1853 set out the rules for passengers to Australia.

PASSAGES TO AUSTRALIA

The following are the regulations and conditions under which emigrants are to be selected for passages to the Australian colonies, when there are funds available for the purpose.

QUALIFICATIONS OF EMIGRANTS

1. The emigrants must be of those callings which from time to time are most in demand in the colony. They must be sober, industrious, of general good moral character, and have been in the habit of working for wages, and going out to do so in the colony, of all of which decisive certificates will be required. They must also be in good health, free from all bodily or mental defects, and the adults must be in all respects be capable of labour and going out to work for wages, at the occupation specified on their Application Forms. The candidates who will receive a preference are respectable young women trained to domestic or farm service, and families in which there is a preponderance of females.

2. The separation of husbands and wives and of parents from children under 18 will in no case be allowed.

3. Single women under 18 cannot be taken without their parents, unless they go under the immediate care of some near relatives. Single women over 35 years of age are ineligible. Single women with illigitimate children can in no case be taken.

4. Single men cannot be taken unless they are sons in eligible families, containing at least a corresponding number of daughters.

5. Families in which there are more than 2 children under 7, or 3 children under 10 years of age, or in which the sons outnumber the daughters, widowers, and widows with young children, persons who intend to resort to the gold fields, to buy land, or to invest capital in trade, or who are in the habitual receipt of parish relief, or who have not been vaccinated or not had the small-pox, cannot be accepted.

The Negotiator

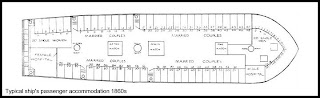

The passenger ship trade was in for a boom period and ship owners diverted whatever available ships they had, or ordered new ships to be built, for the England to Australia run. The Negotiator, a ship of 587 tons built in 1848, had been used on the London to Sunderland coastal route, but was diverted for the Australian rush .

The passenger ship trade was in for a boom period and ship owners diverted whatever available ships they had, or ordered new ships to be built, for the England to Australia run. The Negotiator, a ship of 587 tons built in 1848, had been used on the London to Sunderland coastal route, but was diverted for the Australian rush .On 14 May 1852 the Negotiator, under the command of its Master, J. Young, left London bound for Melbourne. On board was the twenty one year old bachelor, William Cosstick. William had decided to give up his work as groom at the Cold Harbour Farm and venture into the unknown.

On almost exactly the same date in mid May 1852, but half a world away, John Hamilton and his brothers Richard, Robert and Alfred, left Adelaide to walk to the gold fields of Victoria. The Hamiltons and Cossticks did not know each other then. But ten years later the two families would be united by two marriages .

William Cosstick arrived in Melbourne on 30 August 1852 . On that same day the Hamilton brother’s father, Richard Hamilton, died at his home south of Adelaide. The brothers returned home from the gold fields and did not return again until 1856. The Argus reported that the Negotiator had had "rather a tedious passage from Plymouth, having experienced several mishaps". But then it added that "Neither births nor deaths took place." On board the Negotiator, apart from an assortment of cargo consigned to various Melbourne merchants, was £10,000 worth of coinage on private consignment.

What did William Cosstick do once he arrived at Melbourne? Did he come with friends or alone? Did he leave England knowing that his brothers were to follow him? Did he imagine that he was leaving Surrey, the Garden of England, to settle in what had been described as Australia Felix - the garden of Australia? Could he have imagined the vast difference in conditions that he would face on the gold fields of Central Victoria? We might speculate as to the answers to these questions. We might imagine the family discussions that took place before he finally made the decision to leave England. Did some attempt to persuade him not to go, or was there great enthusiasm for his adventure?

After William arrived at Melbourne he surely wrote home giving his impressions of the town and the prospects he imagined were to be found in the colony. If he wrote home within one or two weeks his family would receive his news by Christmas. Whatever he wrote the family must have received a favourable account of Melbourne and the prospects of life in the colony, for, on 22 January 1853, his older brother, Henry Cosstick, Henry’s wife, Sophia, and another brother, George, sailed from London on board the Appleton.

The Appleton

The Appleton was a medium sized vessel of 967 tons, mastered by J.A. MacDonald . This ship, nearly twice the size of the Negotiator, could accommodate up to 224 passengers. The Master allowed provisions for 165 adult passengers and the Melbourne Argus reported the arrival of a total of 201. The ship arrived at Melbourne on 27 April 1853.

Both Henry and Sophia listed their occupations as oilmen on the shipping register. Nineteen year old George gave his occupation as a manservant . They had clearly come to the decision that life in Australia offered greater potential than continued life in domestic service in England - which is what the Emigrant’s Friend had been telling people for some years.

Henry Cosstick had married Sophia Edwell nine years earlier at All Souls Church, St. Marylebone, London, on 9 April 1844 . They had two children, Henry, who was baptized on 26 September 1846, and Ellen, baptized on 23 April 1848 . Neither child accompanied the couple to Australia. It is possible that both died as infants in England before 1853. Henry and Sophia had no other children.

Arriving at Port Phillip Heads on Wednesday 27 April 1853 the passengers on the Appleton would have been dismayed at the site of the barque Sacramento which had come to grief on the Port Lonsdale Reef at three o'clock in the morning. The Geelong Advertiser explained what had happened.

The barque Sacramento, Holmes, master, from London, with 250 government immigrants arrived off the Heads yesterday. At about three o'clock a.m. the ship struck upon the Point Lonsdale reef, about one mile from shore and four from the lighthouse.

The long-boat, life-boat, and two smaller boats were immediately hoisted out, and the landing of the immigrants commenced. Some were taken to the shore and others landed temporarily on the reef. The news was brought to Geelong yesterday afternoon by the Rev.Mr.Lord, chaplain to the Sacramento. When he left the pilot station yesterday morning at nine, the boats were busily engaged in landing the immigrants, but as a heavy surf was running, the process was necessarily slow…

The condition of some of the poor creatures crowding into the boats, many of them in their night dresses only, was truly pitiable. From the ship’s position she is not likely to be got off, and in the meantime the immigrant’s luggage and cargo is in jeopardy; indeed as the weather has since been very squally, the vessel has most likely already gone to pieces…

Several vessels passed up the Western Channel yesterday, so that the news of the wreck will have reached the Government .

One of those ships was the Appleton.

Captain Holmes and the Pilot, Mansfield, went back to the ship to salvage £60,000 in coins, which they managed to do with great difficulty and risk as the sea was already washing over the vessel .

Captain Holmes and the Pilot, Mansfield, went back to the ship to salvage £60,000 in coins, which they managed to do with great difficulty and risk as the sea was already washing over the vessel .We might imagine the scene on board the Appleton as the passengers passed the stricken vessel and wondered whether they might suffer the same fate only hours from their destination. But they arrived safely at Melbourne later that day, as did some two thousand seven hundred other immigrants.

The Argus found the massive influx worthy of comment under the heading of

THE ENGLISH INVASION

Upwards of two thousand seven hundred souls were added to our population by vessels announced in yesterday’s shipping inltelligence. The circumstance would have excited some little attention in ordinary times; but in this era of miracles nothing would startle us…there can no longer be any mistake about the English invasion….every southerly wind that blows a fresh fleet of British ships into our harbour, gives us decided proof of the amazing extent to which it is being carried out…To the newcomers themselves we would say that, however unfavorable the first aspect of colonial life may be to them, they must not be discouraged. The adverse circumstances that seem to thicken around them at the outset are unavoidable, and can all be dispelled by courage and perserverence. Let the newcomer take the first employment that offers; let him be careful of his earnings; let him bear temporary discomforts with cheerfulness; and before long he will find that Victoria offers the finest field in the whole world for the man of industry and character, and that he has not made a mistake in joining the British industrial army which has come to invade Australia.

But such words of encouragement had been preceded only a day earlier by a more objective report of the arrival.

Perhaps as large a number of immigrants as ever arrived on these shores at one time, landed yesterday. Between seven and eight o’clock last evening, the road from Cole’s wharf was crowded with immigrants just landed from the English vessels in the Bay. Groups of men, women and children, plodded their way through the mud and thick darkness to the Government Depot, and Heaven knows where else, in the hope of finding a night’s lodging. On the wharf itself, the scene was really distressing. Amid the unsteady glimmer of a lantern or two – which faintly illuminating a few square feet of ground, only served to increase the darkness everywhere else – many hundreds of human beings groped their way ashore, clambering over heaps upon heaps of luggage, bales and goods of every description, the slippery wharf beneath their feet, the silent river rippling past, and only too thankful to escape without loss of life or limb from the perpexing dangers around. Numbers of these immigrants must have passed the night in sheds, behind logs of wood, or inside the large boilers lying about the wharves. We may observe that there is not a single lamp along the whole range of the wharves, which is a truly disgraceful fact.

Having arrived at Melbourne with thousands of others Henry, Sophia and George Cosstick did what most new arrivals did, they looked for somewhere to stay. Did they bring a tent? Did they sleep behind a log, or in a boiler? The next day they placed an advertisement in the newspaper in the hope that their brother William would see it and learn of their arrival.

Having arrived at Melbourne with thousands of others Henry, Sophia and George Cosstick did what most new arrivals did, they looked for somewhere to stay. Did they bring a tent? Did they sleep behind a log, or in a boiler? The next day they placed an advertisement in the newspaper in the hope that their brother William would see it and learn of their arrival.WM. COSSTICK's brother has arrived at Melbourne; either apply or address to the Post-office .

A week passed without response and a second notice was placed in the Argus on 5 May.

W.COSSTICK - Two brothers have arrived at Melbourne, to be found at Canvas Town .

Their brother must have seen the second message for no more notices were necessary.

To the diggings…

Within a short time of their arrival in Melbourne, perhaps weeks, certainly within a few months, it seems that the Cosstick brothers, William, Henry and George, and Henry's wife Sophia , headed for the Central Victorian gold fields. Most attention in mid 1853 was on Forest Creek at Castlemaine, but the centre of interest was shifting daily as new rushes occurred.

While we do not have any letters or diaries written by the Cossticks immediately after their arrival in Melbourne there were others who wrote about their experiences. One of these was Seweryn Korzelinski, who arrived on the Great Britain towards the end of 1852 and soon travelled to the Forest Creek and Maryborough gold fields.

While we do not have any letters or diaries written by the Cossticks immediately after their arrival in Melbourne there were others who wrote about their experiences. One of these was Seweryn Korzelinski, who arrived on the Great Britain towards the end of 1852 and soon travelled to the Forest Creek and Maryborough gold fields.Describing his arrival at the port of Melbourne Korzelinski writes

The port is unlike anything I’ve ever seen so far. There are no signs of boats offering fruit, or boats with people curious to see the new arrivals. Possibly there is no fruit in Australia and as for the people, apparently they are too busy for idle excursions.

After reacting with some dismay at the inflated prices in Melbourne, and having to wait another two days before his luggage could be ferried into the town, Korzelinski finally arrives in Melbourne and camps with his companions on the south side of the Yarra in the area known as Emerald Hill.

A few days passed while we made preparations for the trip to the mines, and meanwhile I visited the surroundings and the town…one day surely it will be the size of London, if not larger

The streets are full of carts and wagons pulled by horses and oxen. The empty ones return from the mines, the loaded ones are leaving town accompanied by groups of a few or more miners. A few lucky miners who struck it rich are in town to spend their money as fast as possible. Some of them walk with a superior smile watching the new chums. Some, under the weather, drive in carriages accompanied by some well-dressed nymph… .

Having brought a cart from England with them, and purchased a horse to pull it, Korzelinski’s party was finally ready to set off to the gold fields on 26 November 1852. They went only as far as Flemington and discovered that neither their horse nor cart was up to the journey. After arranging with another traveller to have his horse pull the cart they again set off.

On the second day out they reached a group of three buildings – a house, hotel and store – the town of Keilor. By nightfall they had reached the Black Forest. On the third day they passed Mount Macedon and the town of Bush Inn where the axle of their cart succumbs to the strain and broke. After unpacking the wagon, removing the axle and carrying it back to Bush Inn to be repaired, they hoped to be on their way once more. But alas, the second axle broke. This time travellers informed them that Five Mile Creek was only half a mile up the road. So they once again waited for repairs to be made.

On the second day out they reached a group of three buildings – a house, hotel and store – the town of Keilor. By nightfall they had reached the Black Forest. On the third day they passed Mount Macedon and the town of Bush Inn where the axle of their cart succumbs to the strain and broke. After unpacking the wagon, removing the axle and carrying it back to Bush Inn to be repaired, they hoped to be on their way once more. But alas, the second axle broke. This time travellers informed them that Five Mile Creek was only half a mile up the road. So they once again waited for repairs to be made.In the meantime heavy rain had made the roads extremely difficult and they spent a day and a night at Five Mile Creek waiting for the mud to dry out. They then proceeded through the Black Forest, meeting several would-be bushrangers on the way, and then to Kyneton. Finally, on 3 December, after seven days, they reached Forest Creek.

It might be imagined that the Cossticks experienced a similar, though less eventful, journey on their way to the gold fields in mid 1853 .

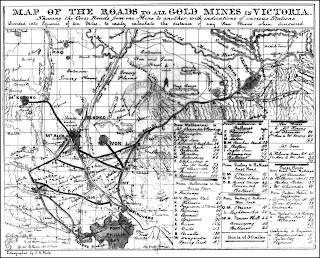

The Hamiltons, journeying from Adelaide in mid-1852 were probably also heading for Forest Creek or Mount Alexander. We might picture them, among thousands of others, making their way across the desert and through the flooded rivers on the journey from Adelaide. The advertisements in the papers all proclaimed Mount Alexander and Forest Creek as being the places to head for. But the Hamiltons may not have reached Forest Creek, for they seem to have been distracted once they reached Daisy Hill forty miles to the west .

Cosstick and Windy Jack at Tarrangower

A few miles north west of Forest Creek were the Bryant’s Ranges, or Tarrangower. Captain John Mechosk has been given credit for the first discovery of gold at Tarrangower in June 1853. The Government in fact awarded him a £500 reward for his efforts some years later.

However, despite Mechosk’s own account of how he discovered the gold given a few years later to the Parliamentary Select Committee looking into his claims, it seems possible that somebody else may have discovered gold at Tarrangower before Mechosk. And it may not be entirely outrageous to suggest that one of the Cosstick brothers was that person.

After finding gold at Jones’ Creek (Dunolly) Mechosk moved on to the Bryant’s Ranges, where he later claimed to have discovered gold as early as June 1853. In July he found gold at the McIntyre Ranges (Kingower) and in August at the Simpson’s Ranges (Maryborough). He then moved back to Bryant’s Ranges later in 1853.

On 28 September 1866, three years after Mechosk’s death in Queensland, the Tarrangower Times, in reviewing the town’s history, suggested that Mechosk was not entirely deserving of his fame, at least as far as the Tarrangower discovery goes.

The facts are well known to old residents of the place - that the Captain was merely instrumental to the discovery, and that he did not succeed in discovering gold until some time after those more fortunate had made on this gold field large sums of money and, in some instances, fortunes better known by the mining fraternity by the significant title of “a pile” .

So, if Mechosk was not the first to discover gold at Tarrangower, who was?

While still looking for gold in the Bryant’s Ranges in late 1853 Mechosk regularly travelled with his horse and dray to Barker’s Creek in order to obtain provisions. As might be expected, it was rumoured that Mechosk may have discovered gold but was keeping the fact quiet. A group of miners from Barkers Creek decided to follow the tracks of the cart wheels and see what Mechosk was up to. They got as far as Tarrangower by 6 December 1853. Several others arrived two days later.

The first party, having located Mechosk’s general position, and being “within coo-ee of the prospectors”, became lost in the dense bush and it was not until 11 December that they actually came face-to-face with the Captain - who was apparently not at all pleased with their intrusion.

Mechosk’s party had sunk a shaft at the foot of Swiper’s Reef. It had yielded nothing and the group was in the process of going deeper but again nothing was found.

In the meantime, having disturbed Mechosk’s isolation, the party from Barker’s Creek decided to sink a few holes of their own in what they called Long Gully. The Tarrangower Times continues.

To cut the matter short, washdirt yielding half an ounce to the tub was found in nearly every claim, and this was soon getting noised abroad, before the end of the month “Rush-Ho” had been sounded, and by the time the festivities of Christmas and New Year were over, there were no less than 20,000 diggers and others congregated on Bryant’s Ranges.

The initial sinking in Long Gully was apparently before Mechosk had found any gold himself. If we believe the Tarrangower Times, Mechosk had not been successful at the time he was discovered on 11 December 1853. Unless he was keeping his discovery quiet. The Barker’s Creek group then sank some holes in Long Gully and found gold. By that time it would have been getting on to the middle of December.

Who was in the Barker’s Creek party?

A contemporary account by J.G.Moon continues the story. Unlike the Tarrangower Times, Moon apparently did not question Mechosk’s claim to have been the first to find gold and then states that

The next place opened was Long Gully, and two men who had the luck to find payable gold were Costick and Windy Jack. Their claim was opposite to where the Welcome Quartz Claim now is, and the gold was obtained at a depth of ten feet. On the discovery, the few that stood around, anxiously awaiting the result, set up three hearty cheers on seeing the rich prospects fof the first dish, and immediately marked out their claims and began sinking. Christmas drawing near, they agreed that they would spend it in Castlemaine, but on no account say anything about their discovery....on their return some days afterwards, what was their dismay and disgust at finding their claims had been discovered and worked out .

Such was the luck of the gold fields! But such events, and worse, were not uncommon.

We might speculate as to who Windy Jack was and just how he got his name. It was not John Cosstick, as he had not yet arrived from England.

Was it one of the Cosstick brothers who first discovered gold at Tarrangower? If we accept the Tarrangower Times account that Long Gully was in fact the first place where gold was found then that places “Costick and Windy Jack” either with the Barker’s Creek party when they went to Long Gully, or before them. If gold had already been discovered in Long Gully why would the Cosstick party go to Castlemaine and want to keep it quiet?

Was it one of the Cosstick brothers who first discovered gold at Tarrangower? If we accept the Tarrangower Times account that Long Gully was in fact the first place where gold was found then that places “Costick and Windy Jack” either with the Barker’s Creek party when they went to Long Gully, or before them. If gold had already been discovered in Long Gully why would the Cosstick party go to Castlemaine and want to keep it quiet?They would probably only want to hide the news if nobody else had discovered gold in the same place. But, as Moon relates, their claim was discovered over Christmas, and, as the Tarrangower Times account states, “before the end of the month” the word was out and after Christmas and New Year up to 20,000 converged on the place.

While we might feel sorry for Cosstick and Windy Jack at the loss of their claim, we should be aware that they took the risk when they left it to go in to Castlemaine. The regulations governing mining claims required that a claim had to be worked for at least a few hours every day. If a claim was left unattended for over twenty-four hours then it could legally be claimed by somebody else . Such a regulation meant that many claims were lost simply because the two or three miners working it had to go into town for supplies or were away for some other reason. When the original claim holders returned to find other miners working the claim arguments, and violence, frequently broke out. Complaints could be made to the Goldfields Commissioners but the hearing of complaints took some time and claims could not be worked while a hearing was pending. The miners often decided to settle the disputed claim by other, more direct means .

After returning to Tarrangower from Castlemaine what did the Cossticks do? It is unlikely that having their claim jumped caused them to give up. Certainly disappointment and anger may have been their reaction. They probably kept searching. There was, after all, more to find. Were they among those who, as the Tarrangower Times claimed, had made “a pile” before Mechosk found anything?

A few weeks later, in January 1854, there was a huge rush to a place called The Porcupine, another part of the Bryant’s Ranges. There was plenty of gold, but no water, at the Porcupine and water was soon selling at the inflated price of two shillings and six pence a bucket. In addition to being short of water, and probably short of gold, many diggers soon found themselves short of cash and were forced to remain on the field to do the best they could.

When William Howitt arrived at the diggings early in 1854 he described them as

A host of tents, whitening all the valley, as far as we could see... When we came up to the tents we found them surrounding a part of the valley which was all completely dug up, and throngs of diggers at work .

All here was bastle, and man thronging on man... We could see that thousands of holes had been put down which had proved shicers, that is, blanks; but in the middle the white heaps of pipeclay which were thrown out, and the windlasses at work, showed that there the diggers had struck the gold.

When we came to traverse the whole of the diggings we found them estending to about three miles along this valley, which at the upper end turned off to the left and again descended in the opposite direction towards the Forest Creek road, called properly Long Gully. All the way the land had been turned up with an amazing activity for so short a time, only a few months.

The majority of the holes had yielded little or nothing; others had evidently yielded well, and it is said, very well. We were assured that some men had taken as much as £1,000 out of one hole.

The mischief is that it is evidently a lottery, with far more blanks than prizes. Accordingly, while same said that a few were doing well, the majority denounced the diggings as not worth the name - as having neither gold nor water to work it if it were there...

As we came down Long Gully on the way to Forest Creek we saw heaps of stuff which had been piled up during the summer to await the rains of winter. The diggers have constructed dams across the gully to catch the winter rains.

![1853 Goldfields Map of central Victoria showing whereabouts of Cosstick Brothers [Very large image]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhtFYAUCqXyJnoywOhFQ_FeoJ7i68TSp0cUajJb6N1SU0NmNpm4Uh7L6Q3J2FCcD2bWy0ryLpQx7IFHaTHYw9ByVJYbhMyCPMttS2zY-SZTR5e1_6TpO8OC2nKsSJ8U3Y8T0LAy14hZBMk/s320/1853MountAlexander1.jpg) But the Tarrangower rush was nearly at an end. There were a few who did well. There were many who struggled just to survive. And to survive sometimes involves taking risks and moving on. By the end of 1854 those who were struggling at Tarragower were tempted to try for better luck at the Simpson’s Ranges, some twenty miles to the West. And it was at the Simpson’s Ranges diggings that the town of Maryborough was soon established.

But the Tarrangower rush was nearly at an end. There were a few who did well. There were many who struggled just to survive. And to survive sometimes involves taking risks and moving on. By the end of 1854 those who were struggling at Tarragower were tempted to try for better luck at the Simpson’s Ranges, some twenty miles to the West. And it was at the Simpson’s Ranges diggings that the town of Maryborough was soon established.Gold had been found in the Simpsons Range’s at least as early as June 1854 and at nearby Four Mile Creek. . John Bull, the Goldfields Commissioner at Castlemaine, visited these goldfields, which collectively became known as Maryborough, in July 1854 and found 3,000 diggers at work . It was his opinion that a recent area opened at Daly’s Flat, four miles to the south towards Daisy Hill, would eventually connect the two gold fields. By 19 August 1854 the Maryborough population was 20,000 while those at Tarrengower numbered a mere 3,500 . A week later the population at Maryborough had risen to 23,000.

By October 1854 rushes had occurred towards McCallum’s Creek to the south and towards the Bet Bet Creek on the west, and by November a major rush to Creswick’s Creek took many miners both from Maryborough and Amherst . In December a new rush at Joyce’s Creek, or the Alma, brough many back to the area. By April 1855 there were 14,000 at the Alma .

Between April and May 1855 there were so many incidents of bushranging and armed robbery, assault and even murder, at both Alma and Amherst that the miners decided to take their own steps to protect their lives and property . On 29 May 1855 the Maryborough Mutual Protection Society was formed following the formation of a similar group at Alma. On 15 June 1855 matters boiled over at Alma with one John McCrae nearly being hanged by an angry mob of Irishmen after he jumped a deserted claim . McCrae was rescued but over the next few days some 3,000 “Allies”, many of them armed, and all angrily opposed to the Irishmen, massed at Alma and Adelaide Lead.

It would seem quite reasonable to surmise that the Cossticks, having been to Tarrangower, perhaps doing modestly well, but not necessarily so, moved on to Maryborough in 1854 or 1855, possibly experiencing the riots at Alma. And after Maryborough to Amherst by 1856 .

The movement of diggers on the goldfields is almost impossible to follow. They usually left no permanent records. Letters were addressed to Post Offices for collection at some unknown date. The Cossticks certainly had plenty of letters addressed to them between 1852 and 1860 - but all for collection at the General Post Office in Melbourne .

The Cossticks and Eureka

Back in August 1851 Governor La Trobe had introduced a licence system on an attempt to regulate the rush of workers to the gold fields. For thirty shillings per month diggers could work a claim eight feet square. The high price was an attempt to deter workers from leaving their employers. But the very fact of issuing licences meant that individuals rather than syndicates or companies were encouraged to search for gold .

From the beginning would-be prospectors protested against the high fees. Many refused to purchase the licences. But the Government, in need of cash and under pressure from business interests, doubled the licence fee to £3 from January 1852. Diggers immediately united in protest. For the next three years resentment simmered until the revolt of Eureka at Ballarat in 1854.

In the meantime the Government attempted to enforce its licence system, and other laws, by deploying police on the goldfields to collect fees and prosecute those without licences. Many of the police officers of 1852 and 1853 were former convict superintendents from Tasmania, and many of the policemen themselves had former experience on the other side of the law. The methods used by the police to enforce the law on the gold fields aroused resentment. Sly grog tents were burnt down, but not until the police had taken their share of the grog and bribe money. Protection payments frequently changed hands.

The police activities that aroused most resentment were the licence hunts. Licence searches often caught the newly arrived or the non-digger who was then dragged off to the Commissioners tent and held in custody or chained to a tree until the Commissioner had time to hear their case.

For most of the diggers, however, resentment at the treatment handed out by the government and the police took second place to the prime task of finding gold. Occasionally public meetings would be held, such as those at Castlemaine, Bendigo and the Ovens gold fields in 1853.

In June 1853 the Anti-Gold-Licence Association was formed at Bendigo and a petition was circulated throughout the goldfields calling on the government to change conditions. Among the five thousand who signed were Henry and George Cosstick. The petition was presented to Charles La Trobe on 1 August 1853 but most of the demands were rejected .

In August 1853 diggers at Bendigo and Heathcote refused to purchase licences and wore red ribbons to indicate their refusal to the police and challenge arrest .

The government relented, slightly, and reduced the licence fee to £1, £2, £4, or £8 for one, three, six or twelve months. A recommendation from La Trobe that purchase of an annual licence should carry the right to vote was rejected.

Despite the reduction in the licence fee, during 1854 there was even greater resistance to paying it among the diggers. The government’s reliance upon income from licences had reached such a degree that Sir Charles Hotham, the new Governor, after touring the gold fields, decided that the diggers were generally doing quite well and should be compelled to pay up. Police licence hunts were increased with a reciprocal increase in digger resentment. By October and November 1854 huge meetings were being held on the Ballarat gold fields. The revolt culminated at the Eureka Stockade on 3 December 1854.

By mid 1855 the licence fee had been abolished and replaced by a £1 Miner’s Right which both allowed mining on a claim and gave the right to vote - the first elections for both the Legislative Council and Assembly taking place between August and October 1856. The Goldfields Commissioners were replaced by a system of Wardens and elected Mining Courts.

Where were the Cossticks during all of this turmoil?

The rest of this chapter is in the book.

Footnotes

Full references and sources are available for this information and are published in the book. Please email me if you would like source references.

No comments:

Post a Comment